January 2020

Silvia Waisse, researcher from PUC-SP.

The comparative approach has been advocated to overcome some flaws proper to case studies. In the article The comparative approach: a solution to the limitation of case studies?, Silvia Waisse, from PUC-SP, Brazil, and Motzi Eklöf, independent researcher formerly affiliated with the Karolinska Institutet, Sweden, performed a comparative study between both countries.

After conducting careful case studies of the early spread of homeopathy in Brazil and Sweden in the early nineteenth century, they found that consideration of broader contexts, socio-historical and scientific determinants, and interactions among actors provide more accurate pictures of episodes in the global history of medicine.

“We addressed the spread of homeopathy through a comparison of the cases of Sweden and Brazil, where homeopathy eventually met diametrically opposed fates”, explains Ms. Waisse.

The parameters used for comparison are the standard for studies on the early spread of homeopathy, such as the so-called ‘introducer(s),’ reception by the medical and academic community, the government and society at large.

The results suggest that analysis of contexts, determinants and the interactions of practitioners and institutions representing different health care approaches, dominant or alternative, seems to provide more accurate pictures of different moments of the global history of medicine.

This study is a part of a larger research project on the transnational transit of scientific knowledge jointly conducted by Uppsala Universitet, Karolinska Institutet and PUC-SP funded by STINT, Sweden, and CAPES, Brazil.

Read the interview with Silvia Waisse by HCSM journal blog.

What is the purpose of your research and how does it fit within the field of the history of global medicine?

We compared two timepoints in the spread of homeopathy: early arrival in Sweden and Brazil in the 19th century, the so-called “golden ages” in both countries at about the turn and beginning of the 20th century. This research is part of a larger collaborative Project (University of Uppsala, Karolinska Institutet and Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo, funded by STINT and CAPES) on the transit of scientific knowledge between major European centers with their (former) colonies, as well as with European areas without direct participation in colonial dynamics.

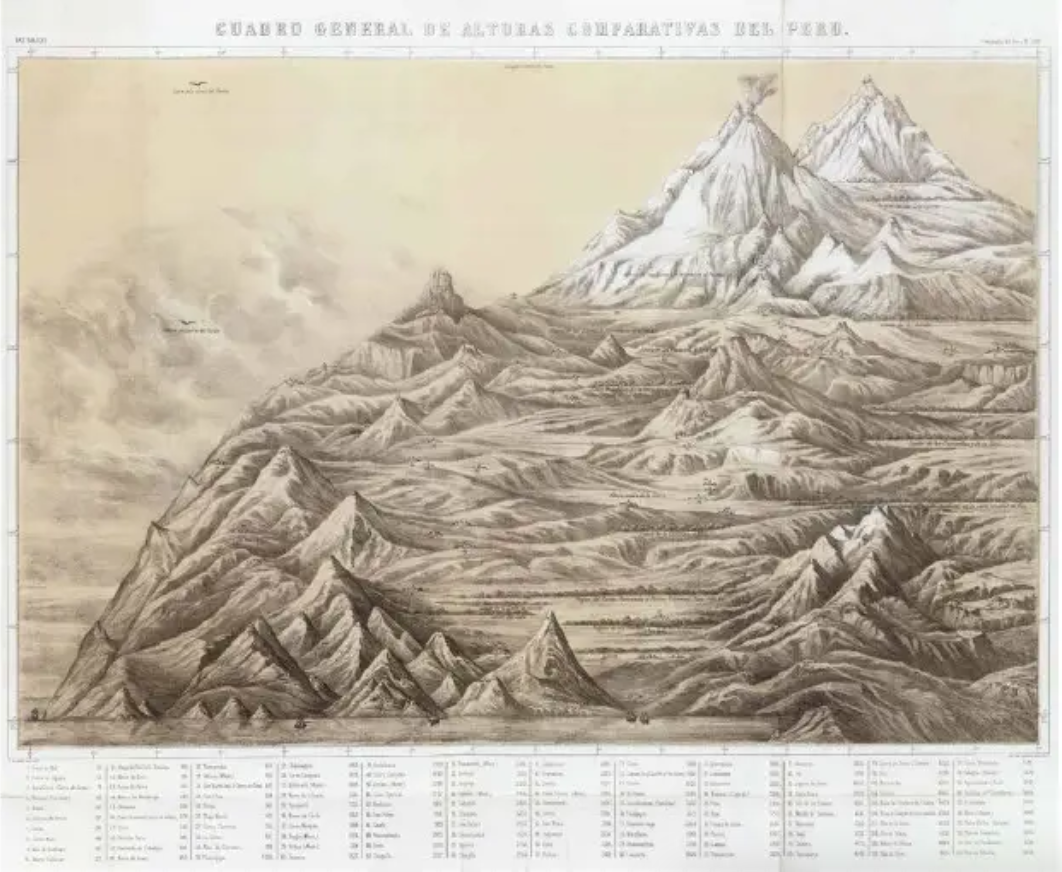

The image illustrates the spread of homeopathy across the globe by decades.

What was the methodology used and which criteria led you to opt for it?

We used the comparative approach. Traditionally, national histories of homeopathy have been approached as individual case studies (including some performed by us too) resulting in a wealth of scholarship. However, as Martin Dinges pointed out, this approach has some epistemological and methodological flaws: (1) scattered evidence is taken as sufficient proof for a general trend; (2) exaggeration of alleged “crises” in conventional medicine and underestimation of the ability of dominant systems to recover; and (3) underestimation of the broader socio-historical context and assumption of a unilinear, teleological view of historical developments.

In contrast, the comparative approach is likely to control for the errors resulting both from the wishful thinking proper to the internal history of homeopathy (and other modes of complementary and alternative medicine) and from established history writing downplaying homeopathy in medical history on sometimes ignorant grounds. In particular, since proper attention is paid to the necessary contexts, it helps overcome problems derived from the number of actors, duration of periods of observation, and size of geographical units.

Can you comment on the flaws detected by this study on the epistemological and methodological approaches most commonly used?

I wouldn’t speak of “flaws,” but of historiographical reasons. Older HSTM focused a lot on “discoverers”, “paternity”, “priorities”, etc., and in the case of homeopathy, on the so-called “introducers”. Over time, this view was seriously criticized (it cannot be discussed here, because it would take hours of writing!) but current historiographical approaches consider sociohistorical context and epistemological aspects together in analysis. So, for instance, along our research we came to realize that some of these “introducers” are rather mythical figures. In turn, we found that the academic training of homeopathic practitioners (university trained physicians or lay) played a substantial role in the institutionalization – or not – of homeopathy in different countries.

What are the results of your research and how do you expect them to contribute to the study on the history of global medicine?

Our results strongly suggest—corroborating Dinges’s observations—that the analysis of contexts, determinants, and the interactions of practitioners and institutions representing different health care approaches, dominant or alternative, seems to provide a more accurate picture of different moments in the global history of medicine.

Then, several factors are commonly cited in the literature as reasons for the acceptance or refusal of homeopathy in different countries. Most such factors are purely epistemological: scientific (or not) status of homeopathy, plausibility of the action of high dilutions, the similia principle, and so forth. Our research indicates that the label “scientific” varies as a function of the overall social context, and that many other variables, including institutionalization of medicine, medicalization, political interests, public health concerns, health care provision systems and the population’s rights, among others, have equal, if not greater, weight on the attitude vis-à-vis non-mainstream medical approaches.

Finally, while HSTM certainly has intrinsic value, given the unstable status of homeopathy around the world, our comparative studies are useful to understand the current situation of homeopathy in Sweden, where it failed to institutionalize at all, and Brazil, i.e. one of the most successful cases.

Therefore, our research can be relevant in STS and also for healthcare policymakers. Especially at this exact moment, when TCIM has earned a place within the WHO International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) of mandatory use for Member States, to enter into force on 1 January 2020, while the medical and scientific establishment has already voiced its disagreement and is preparing to have WHO reverse this decision.

Read the full article here.

Read our full issue: HCSM vol.26 no.4 Oct./Dec. 2019