December/2019

Dr. Jethro Hernández Berrones

“One of the beauties of studying healing systems such as homeopathy is that they serve as a lens to understand the social and cultural values a particular community, society, or country has regarding disease and medicine,” affirms Dr. Jethro Hernández Berrones, Assistant Professor of History in Southwestern University (Georgetown, USA).

In his paper Breaking the Boundaries of Professional Regulation: Medical Licensing, Foreign Influence, and the Consolidation of Homeopathy in Mexico, published in HCSM journal (vol.26 no.4 Oct./Dec. 2019), Dr. Jethro Hernández Berrones examines how homeopaths irrupted in the Mexican medical profession disrupting nationalist discourses and practices by Mexican doctors aimed to provide Mexican medicine to Mexican patients.

Homeopaths in Mexico engaged with foreign academic works, imported therapeutic approaches and products, and established relationships with professional organizations abroad, while accommodating to licensing policies that changed as the country defined its position in the global political economy. Homeopaths’ ambivalent position determined their ability to navigate both the professional and popular medical world and create a space for themselves among modern medical institutions.

Using a variety of sources such as academic journals, official correspondence and documentation from Public Health and Education offices, and programs of international homeopathic meetings, he interlaces the scattered references to homeopathy in the historical record with the solid scholarship of institutional medicine in Mexico.

Read below the interview with Dr. Hernández by the HCSM journal blog.

How was your historical research done? What methodology did you use?

In my doctoral dissertation, I studied the historical development of homeopathy. I had naive understandings about the tensions between medical science and homeopathy that developed into social concerns. If tensions between medical science and medicine existed, why did governments sponsor homeopathic institutions in Mexico? This question led me to write a master dissertation which was an internal history of homeopathic practice and institutions. I wanted to understand under which terms homeopaths claimed their system and practices as scientific.

In this work, I described their ideas, institutions, and conflicts with other physicians. I did not pay attention to external or social aspects that framed these developments. I used their publications and the patchy traces homeopaths left in the archives. With more experience as a historian, I focused on the social and cultural aspects that framed the constant presence of homeopathy as an element of Mexican medicine in my doctoral dissertation. I followed the threads in the archives to trace the struggles homeopaths had with public health offices, the ministry of education, and the judicial system as well as private archives in their struggles to have their institutions recognized.

In this sense, I think that my approach to the study of homeopathy in Mexico borrows from different historiographical traditions, including the social history of institutions and marginalized communities, the cultural history that describes the meaning of using, adopting, and sanctioning homeopathy at the individual and national level, the history of public health institutions that emerged in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and the history of disease, academically trained physicians and the institutions they presided treated homeopathic practitioners as epidemic diseases a modern nation should get rid off and implemented public health strategies to deal with them accordingly.

In the paper I wrote for HCSM, I was challenged by my colleagues and students in the institution where I work to go beyond the national frame and consider the international developments and influences that shaped the adoption and consolidation of a foreign medical system in a nation with ambivalent attitudes towards foreign influences.

The outcome was a work that uses the social and cultural histories of the Mexican medical profession that I crafted in my previous research as a foundation to understand the ambivalent attitudes Mexican doctors had towards medical knowledge, technologies, and staff from abroad. Both homeopaths and their competitors leveraged Mexicans’ allure for foreign to draw support to their cause and gain a place in the landscape of Mexican medicine.

The paper draws close ties between the professional regulation of homeopathy in Mexico with the country’s political situation since the early Republican period. How do you perceive homeopathy today in Mexico?

We live in a completely different historical context that inherited some of the tensions of, but also incorporates some of the lessons learned from the past. In the 60s, Mexicans demonstrated their discontent with government policies that did not fulfill the needs of Mexicans. If social security institutions promised to bring social security, including health security, for all Mexicans, those dreams were lost early in the second half of the twentieth century. Physicians went on strike demanding better salaries and labor conditions to fulfill their job. If Mexicans living in rural spaces never stopped recurring to traditional medicines, an emerging urban middle-class that distrusted institutional medicine turned to new (for them, but old-in-the-national-healing-landscape) therapeutic options.

As the national population grew and healthcare became costly, public health authorities realized the limits of the universal provision of high-quality healthcare for all Mexicans and began looking for options to cope with the demand. As the rest of the world, the notion of other healing approaches as alternatives emerged during these years. Rather than disqualifying them, now health policy makers considered them an option to provide access to healthcare to the population.

A new cultural sensibility towards traditional or indigenous medicine emerged. For instance, the IMEPLAM (Mexican Institute for the Study of Medicinal Plants) was created in 1975 in order to investigate the pharmacological potential of national flora with medical uses.

In this context, policies and legislation that accept homeopathy and other non-biomedical healing approaches were passed. Public health legislation now acknowledges the homeopathic materia medica (the list of homeopathic substances used for specific medical diagnoses).

Homeopaths have organized professional societies and postgraduate programs certified by the ministry of public education. Homeopaths who study at the National School of Homeopathic Medicine and the Free School of Homeopathic Medicine get their state-sanctioned degrees and obtain their medical licenses from the Ministry of Health.

If the population keeps recurring to homeopathy in regular and desperate cases, scholars still regard it ambivalently, today as the did it in the past. Scholars in the humanities and the social sciences are usually open to consider homeopathy’s incorporation into the life of national medical and education institutions, while those in the natural sciences are prompt to disregard what it can accomplish. In the neoliberal era, the legal framework in Mexico gives homeopathy citizenship in the national landscape of medicine, though culturally it is as contested as it was in the twentieth century.

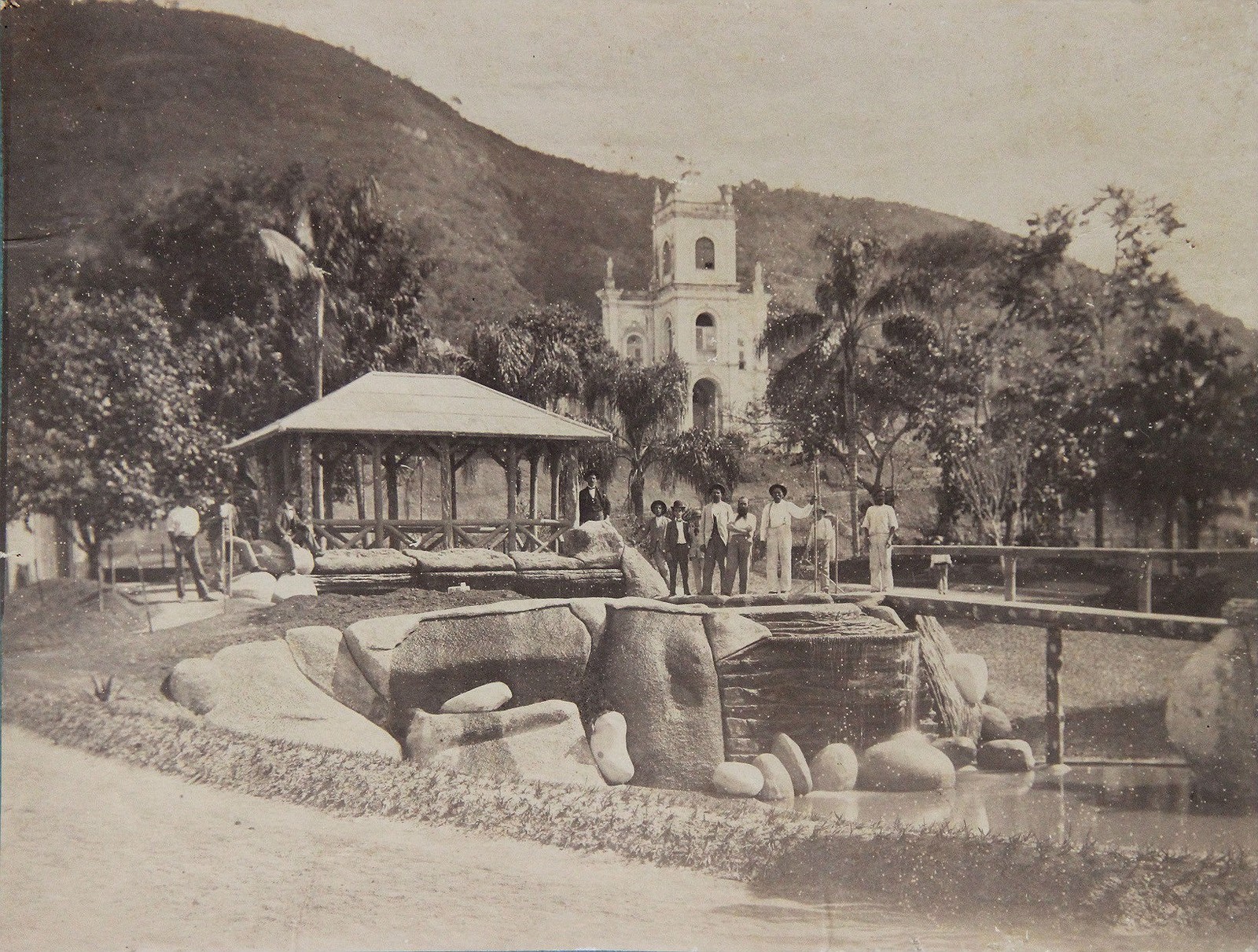

Published in 1935 in the Mexican journal “Accion Medica”. The author is unknown.

What is the reach of Mexican homeopathy at international levels in current times?

As I pointed out in the article, homeopaths earned international recognition in the mid-twentieth century through the pan-american and international meetings they both organized in Mexico and attended in other countries. I haven’t followed the trace of the homeopathic community after this period.

In my interviews with homeopaths during my doctoral research, I learned that Mexico has been used as a model of integration between homeopathic and conventional medical institutions. For example, the National School of Homeopathic Medicine and the legislation recognizing the homeopathic materia medica have served as evidence of Mexico’s integrative policies in international forums such as the World Health Organization’s efforts to integrate traditional medicine in global health policies and statistical tools.

I also learned that Oaxaca, a state where homeopathy has expanded significatively, is a magnet for physicians and lay practitioners who seek advanced training in this system. Finally, I know that Mexican homeopaths have held leadership positions at influential international homeopathic societies such as the International Homeopathic League.

The scope and influence of Mexican homeopathy at the global level remains to be studied.

The paper mentions ambivalent feelings about medical licensing and foreign influence that, albeit these contrasting positions, were used to strengthen homeopathy’s place amidst Mexican medical institutions and society. How do you compare this development with the regulation of homeopathy in other countries worldwide?

One of the beauties of studying healing systems such as homeopathy is that they serve as a lens to understand the social and cultural values a particular community, society, or country has regarding disease and medicine. Recent works in the history of homeopathy in other national settings show similar trends in the sense that homeopathy has been used by patients and practitioners in these settings, such as they did in Mexico. But the reasons for this continued use vary.

For instance, the strong regulatory landscape of the United States pushed homeopathy to the lay consumer and practitioner, where it evolved as a form of holistic healthcare associated with other non-Western health beliefs and stripped off their original medical scientific foundations.

In its struggle for independence, India has adopted homeopathy as a Western medical system in line with indigenous medical beliefs. This way Indian doctors and patients have adapted and adopted homeopathy as an indigenous system in combat with colonial medicine. This dynamic hasn’t been exempted from the tensions that different locally endorsed medical systems, such as Unani and Ayurvedic medicine, pose to the appropriation of a Western medical system.

In other Latin American countries, homeopathy had a later development, though the struggles for institutionalization where similar as in Mexico. Mexico seems to be an intermediate case between the United States and India.

In Mexico, medical and public health authorities have slowly and reluctantly accepted homeopathy throughout the twentieth century. Homeopathy became a parallel medicine. Mexican homeopaths learn an integrative medical system that incorporates both biomedicine and homeopathy. They are able to offer both therapies. It is this dual nature which has allowed them to thrive in Mexico, positioning them as regular medical doctors in the country and as integrative and holistic healers in the context of medicine in the neoliberal period.

As in Mexico, Brazil and India are cited as examples of countries where homeopaths developed contrasting yet effective strategies that opened a space among patients and state institutions in adapting to liberal and state-regulated models of health provision and professional organization in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Can you comment on this parallel in the regulation of the profession within such different countries?

Each national context offers specific regulatory frameworks of professionalized medicine. The parallels between Mexico and other countries, such as Brazil and India, have to do with a general pattern of the provision of medical education and licensing.

In the first half of the twentieth century, medicine was an occupation reserved for literate elites. Individuals aiming at getting a medical education had to have the resources to live in cities with medical schools and the time to dedicate the hours to the hard study of the medical sciences, in addition to the required literacy and disciplinary education. Most families in these national contexts did not have access to the resources to push their children into this professional route. Homeopathic institutions offered a way to pursue a medical education for these usually working-class individuals.

The large demand for this sort of medical training pushed local governments to regulate homeopathic training and practice. This regulatory efforts fulfilled a demand for doctors and medicine that academic medical institutions could not. These countries came up, though reluctantly, with integrative models of professional medicine that made medical training, practice, and health services accessible to more people than the state model allowed.

Following this paper and after putting up this dossier, what will your research examine next?

I am finishing a monograph tentatively titled A Revolution in Small Doses. It details the struggles of Mexican homeopaths to establish and preserve their training institutions during the efforts of post-revolutionary governments to deal with homeopathic practitioners as an epidemic disease.

Read the article Breaking the Boundaries of Professional Regulation: Medical Licensing, Foreign Influence, and the Consolidation of Homeopathy in Mexico by Dr. Jethro Hernandez Berrones.

Read the dossier on Homeopathy in Latin America and Spain: local developments and international networks by Dr. Jethro Hernandez Berrones and Patricia Palma.

Read our full issue: HCSM vol.26 no.4 Oct./Dec. 2019