July 20th, 2021

Interview with Mike Osborne | Vivian Mannheimer

What does it mean to be a scientific superpower? What are the scientific contributions of smaller countries and of traditional ecological knowledge? What does difference mean in terms of our perception of scientists and healers in history? These are some of the topics that will be addressed at the 26th International Congress of History of Science and Technology, between July 25th and 31st, whose main theme is “Giants and Dwarfs in Science, Technology and Medicine”

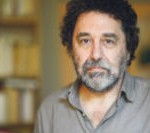

Michael Osborne is the President of the Division of History of Science and Technology of the International Union of History and Philosophy of Science and Technology (DHST/IUHPST). He is also Professor of History of Science Emeritus at Oregon State University.

After three years of planning for an in person Congress in Prague, the pandemic has caused it to take place as a virtual event. The Congress is organized by the Division of History of Science and Technology of the International Union of History and Philosophy of Science and Technology (IUHPST/DHST).

The opening session, titled “What is an epidemic?” was organized by Mike Osborne (President DHST/IUHPST) and Marcos Cueto (Science editor of HCS-Manguinhos and President-Elect DHST/IUHPST). In this brief interview to our blog, Mike talked about the topics that will be investigated at the event and other issues.

Could you explain the main topic of the 26th International Congress of History of Science? Who are the giants and dwarves in science, technology, and medicine?

The Congress theme of giants and dwarfs in science, technology, and medicine is really a challenge to rethink what difference means in terms of our perception of scientists and healers in history. For example, in 1675 the natural philosopher Isaac Newton wrote to Robert Hooke and seemingly credited previous thinkers and scientists with the phrase “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants”. Newton disagreed of course with Aristotle’s account of why objects drop to the earth, the Copernican embrace of circular planetary paths, and of course Descartes vortex theory of celestial mechanics. Another interpretation of this exchange notes Hooke’s diminutive size and posits that Newton may have been poking fun of Hooke. To be sure, Newton was a recluse, and his science was so unlike the team scientific work of today we call Big Science, the sort of work accomplished only by high capacity and high-cost research programs such as the Human Genome Project or the confirmation of the existence of the Higgs Bozon at the Large Hadron Collider at CERN.

Congress participants then will ponder disparities of scale, size, and resource endowment. What does it mean, for example, to be a scientific superpower? What are the scientific contributions of smaller countries and of traditional ecological knowledge? Western science has been promoted as universal knowledge, and the International Science Council, the largest non-governmental organization (NGO) devoted to science, even promotes science as a “global public good.” As historians and science studies scholars, though, we need to ask hard questions about the universality of science and scientific methods. The historical construction and meaning of scientific ideas and scientific and medical ethics differ considerably across locations, time frames, and cultural traditions. The Congress research agenda is varied and stretches from ancient science to modern physics and the histories of scientific instruments.

What are the highlights of the event and the importance of holding a congress like this in the middle of a pandemic?

Let me leave aside for a moment the collective disaster and tragedy of this ongoing pandemic. We began planning the Congress four years ago. In early 2020, my colleagues and I were hopeful that the outbreak would be controlled soon. By spring it became clear that it would be irresponsible to meet in person if we met at all. The decision to go to a virtual format was taken out of a concern for “vaccine equity” and safety of participants as we knew that even if scholars from Western Europe and North American might be able to attend the Congress provided there were effective vaccines, it was certain that others would be excluded and that travel would be restricted for a long time.

Scholars in the history of science, technology, and medicine tend to be social animals. We try out and test new ideas at meetings and we egg each other on in the completion of projects. I am hoping that the virtual Congress will suffice for the time being but I am looking forward to the next Congress which I hope will be in person or possibly in a hybrid format.

How can we understand the pandemic and its implications in light of the contributions from the history of science, medicine and technology?

History of science, technology, and medicine can elucidate many aspects of pandemics. I have already touched on vaccine equity, and I think we could extend that to disparities of funding, access to health care, and much more. But even if every nation had full access to efficacious vaccines, a number of people would decline to be vaccinated. In some countries, people might be compelled to take a vaccine, but in the United States, for example, there would still be people refusing to take it much as they do vaccinations for flu and other infectious diseases. This gets us into questions of policy, leadership, class, and inclusion. It also gets us into misinformation about vaccines.

Epidemics and responses to them may be quite similar but they are not precisely a repeat of the same event. There was no commercial air travel on the scale we have today during the global flu pandemic (1918-1920) and virology was then a young science. Virology would advance as a result of research on polio and the flu pandemics of 1957 and 1968, and that fund of knowledge, coupled with work on other viral diseases and newer mRNA vehicles for delivering therapies, informed the astoundingly rapid development of our current COVID vaccines. I will close by noting that history is quite good at treating past policy blunders and successes. History elucidates the context of events and how people coped with them. It may inform the path forward although each past epidemic or disaster has singularities.

Several contributors at the Congress will engage with the topic of pandemics, how they start, how they end, and how people have coped with them. We’ll start off with a session titled “What is an epidemic?”, organized by Marcos Cueto (science editor of HCS-Manguinhos) and I. We are not the only scholars investigating the history of pandemics at the Congress and attendees interested in the topic can also take in these sessions: “Epidemic Histories in South East Asia,” and De-colonizing Pandemics.

Nice talking with you and I hope that in four years the Congress will have another in-person meeting in either China or New Zealand and it will be equivalent in quality to the high standard set by the organizers of the Rio Congress in 2017!

How to cite this interview: Osborne, Michael; Mannheimer, Vivian. Giants and dwarves in science, technology, and medicine. In: Revista História, Ciências, Saúde – Manguinhos (Blog). Published on July, 21th, 2021. Accessed in [date].

No comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks