June 2013

Jaime Benchimol

Protesters in São Paulo.

Photo: Marcelo Camargo/Abr

HCSM launched itself into the world of social networking precisely at the moment when many cities around Brazil saw an outbreak of demonstrations that have shaken public opinion out of its stupor and given voice to the pent-up dissatisfaction felt by a large share of the public. Social networking as part of science communication is a new experience for us, and a fascinating one that differs greatly from our usual routine of releasing print and digital copies of the content we generally convey. It’s a different type of language, the turnaround is at breakneck speed, our audience is a bit different, and the synergy between readers, editors, and authors takes place at levels and translates into numbers that we are still learning to “surf” (for lack of a better word) – like the novices we see at the beach struggling to balance themselves on the waves. These same waves have swept through the digital world, bringing the realities of our existences into disturbing proximity – and I’m referring to the “protected” reality of an academic journal and the tumultuous and somewhat ephemeral realities of digital collectivities, which are now flooding into the streets and then flowing back into cyberspace loaded with thousands of viewpoints, consensuses, and fragments of information, all spinning around in a dizzying whirlpool.

Protests in Rio. Photo: Tomaz Silva/Agência Brasil

Protesto no Rio. Foto: Tomaz Silva/Agência Brasil

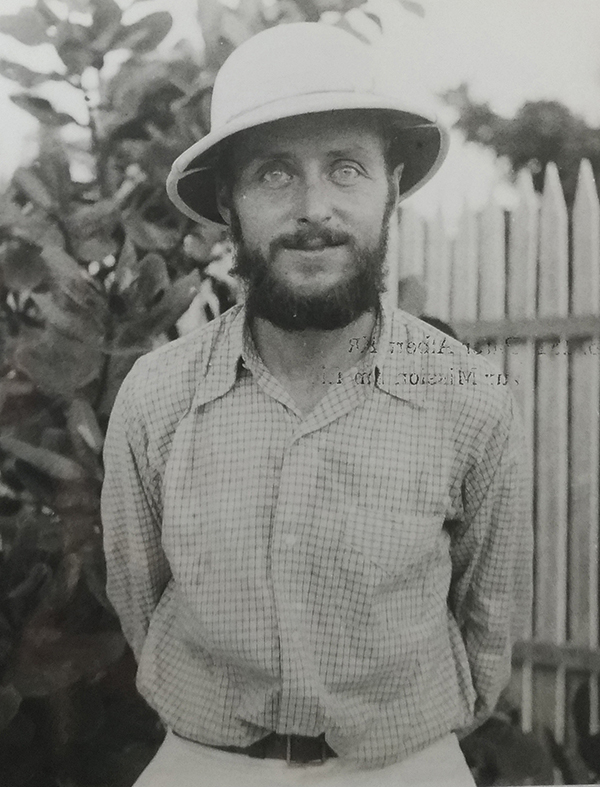

On June 20, Valdei Araujo, one of the most brilliant historians of the new generation, stopped by our offices. He was here at the Casa de Oswaldo Cruz to talk about “What we can still learn from history.” I couldn’t resist the temptation to ask him what he thought about the protests of the past few days – and then Roberta Cerqueira and I left to take part in the one planned (who knows by whom) for that same afternoon. There we witnessed an immeasurable mass of people converging together to completely cover Presidente Vargas Avenue, a major thoroughfare in downtown Rio, five lanes wide in both directions.

It was a beautiful demonstration, packed with young people who were experiencing this active form of democratic citizenship for the first time. But it was likewise packed with folks from the generation that had taken part in major street protests against the military dictatorship and, a bit later, against the Collor administration.

Photo: Ruth Barbosa Martins

(You can’t make history from your couch! #cometothestreets!)

You didn’t see many posters fabricated at print shops but thousands of homemade ones, and you could observe slogans that fingered very specific targets: the generalized corruption within the governing bloc of parties and also within a good slice of the parties that supposedly constitute the opposition; the homophobia of the chair of the Chamber of Deputy’s Human Rights Committee, which has acted as the grotesque spearhead of a dangerous conservative movement that has been nourished by a succession of government administrations through the concession of radio and TV channels, public jobs, and all types of scams and favoritism; plus the dirty tricks played by ministers, governors, and mayors involving the major events scheduled to take place in Brazil’s urban spaces to the inhuman(e) detriment of the population as a whole, but in benefit of discredited under-the-table politics, that is, politics practiced as nothing more than the art of re-election. There were thousands of posters calling for quality education and health instead of grandiose stadiums, and others denouncing the disgraceful initiative by politicians – caught with their hands in the cookie jar – to block state and federal investigations of them.

A beautiful demonstration…spontaneous and very concerned with making its peaceful intentions clear and with rebuffing the small groups that stood sharply apart in the crowd, their intentions of resorting to violence apparent in their dress: their ninja masks, clubs, and iron bars…small groups fixed on doing damage to public buildings and banks, inspired by ideological motivations. Other small groups represented the churlish lumpenproletariate, eager to wreak havoc with everything and everyone, criminals wanting to settle scores with the police and with Rio’s so-called “pacified” favelas (UPPs). Lastly, chemically enhanced bodybuilders who can’t resist an opportunity to engage in acts of muscular cowardice. Vandals without a doubt, and a constant menace to this huge mass of people ready to demand a better, more ethical Brazil.

But there was another contingent of vandals out there in the streets: the police forces who, instead of protecting a peaceful crowd and guaranteeing its lawful right to demonstrate, were spinelessly set loose upon unarmed youths and law-abiding adults, in compliance with the orders of politicians who owe the voters explanations, who do not support democracy, who spew out populist rhetoric, and who in practice are worse than authoritarian – they are nefarious.

We got off at the Uruguaiana metro station, where only a narrow exit lane had been left open in order to force the crowd to leave the station. You could not get a cell phone line on Presidente Vargas Avenue or in the surrounding area so it would be impossible to communicate or to register the crimes that had been planned by the authorities in advance. Those participating in the huge, pacific march had to flee from attacks by squads of policemen on horses and from the aggressive actions of the mayor’s praetorian guards. The editors of this journal, along with Ruth Martins, who works with institutional communication at the Casa de Oswaldo Cruz, later spent hours holed up in a restaurant to escape the fury of the troops, who indiscriminately fired tear gas canisters and bullets at demonstrators as well as at passers-by in the neighborhood of Lapa and in the downtown area known as Cinelândia – even firing into bars where mothers and fathers took refuge with their children.

The powers-that-be and the mayor and governor of Rio de Janeiro have offered proof that they too behave like vandals, foster public disorder, and cynically blame the overwhelming majority of the citizenry for the damages caused, repressing rather than protecting. In the name of what?

Read more:

Why I like Mondays, by Marcelo Badaró

José Murilo de Carvalho: the Brazilian people have woken up from their lethargy

More than narrating these events, we must live them intensely, an interview with Valdei Araujo