Marcelo Badaró Mattos *

Protest in Rio

Photo: Tomás Silva / Agência Brasil

And then the bullhorn crackles

And the captain cackles

with the problems and the how’s and why’s

And he can see no reasons

‘cause there are no reasons.

Tell me why?

I don’t like Mondays

Bob Geldof

What an age it is

when to speak of trees is almost a crime

For it is a kind of silence about injustice!

Bertolt Brecht

Now you can feel the smell of spring in the air.

Osvaldo Coggiola

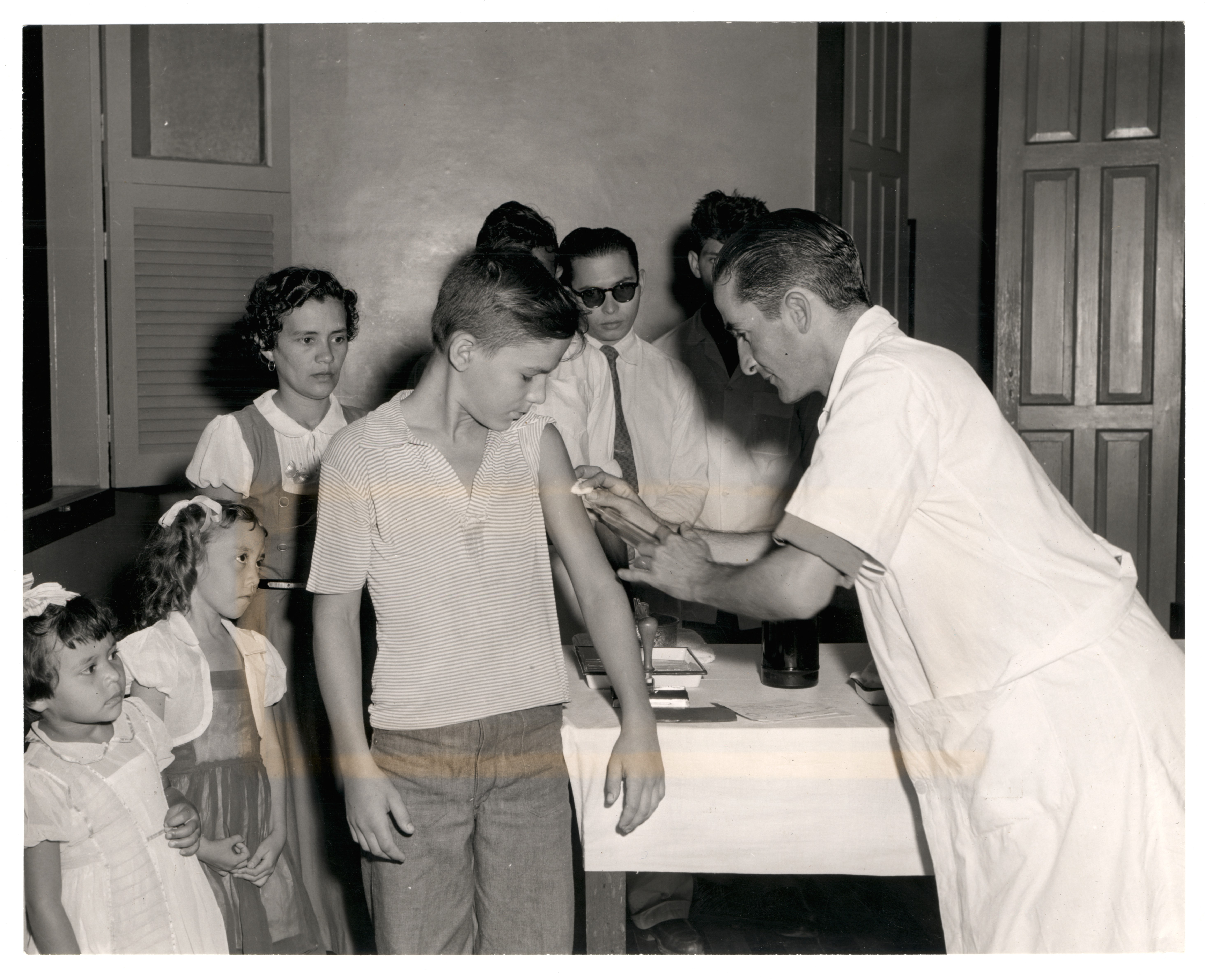

Monday, June 17, 2013, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets in cities all across the nation this afternoon and tonight. Many are still out there as I write these lines. In Rio de Janeiro there were more than 100,000 demonstrators, the vast majority young people, but there were also some veterans of the days when marches of this size were more common. Another good number in São Paulo, many in Belo Horizonte, Salvador, Belém, Porto Alegre, Maceió, and several other cities. In Brasilia, the demonstration covered the roof of the National Congress, mirroring the “Elections Now” campaign of 1984 and the protests against President Lula da Silva’s so-called social security reform in 2003. Brazilians who are scattered around the world – in over fifty cities in Europe and North America – took to the streets yesterday and today to feel part of this same movement.

Protest in Rio de Janeiro.

Photo: Tânia Rego/Agência Brasil

Why? The demonstrations began fifteen days ago, with São Paulo as their epicenter. Their top grievance was the call to cancel the hike on the price of mass transit tickets. Leading the protests was the Free Fare Movement (Movimento Passe Livre), a struggle that has gone on for nearly a decade, championed by students. Its main players are college and high-school students, some of whom are organized in left-wing parties and movements; others are against traditional forms of organization while many shun any reference of this type, donning anonymous masks (from the film V for Vendetta) in paradoxical tandem with Brazilian flags. But there were many workers there as well, unhappy about the price of bus fares and much more. What else?

This is the time of rehearsal for the World Cup, with the Confederations Cup already here. Many folks have been evicted from their homes under the argument that new thoroughfares have to be opened for the Cup, the Olympics – and the appreciation of urban real estate values. And those who spend every day going back and forth to work on jam-packed buses and trains, donating hours of overtime for which they are not paid, have seen no improvement to their lives after all this – to the contrary. What they have seen are governments offering private transportation companies tax exemptions on the one hand while allowing fare hikes that will guarantee steep profits on the other. “Da copa eu abro mão, quero dinheiro pra saúde e educação,” the demonstrators sing – “I’ll give up the Cup, just give me health and education.” All of this is occurring at a time of hyper-appreciation of real estate values and rents, along with across-the-board rises in food prices and the cost of other essential goods and services. So it was no surprise to hear President Rousseff booed at the inauguration of the refurbished Maracanã Stadium.

We can, however, analyze what else lies behind this sudden awakening and these mass mobilizations. One way to get at the heart of it is to pinpoint the main targets of the protests. On TV news reports – especially those broadcast by Brazil’s largest media group, which practically holds a monopoly, that is, Rede Globo, whose reporters have to stay at a distance from protesters and remain anonymous to avoid their hostility – it is apparent that it has become extremely hard to hold to the editorial line espoused some days ago, which labeled the first protests as riots and vandalism. Now they’ve been forced to tone it down and recognize the mass nature of these movements. This is because media monopolies are one of the clearest targets of the protests. People are reacting – albeit in contradictory fashion at times – to what they see as a clear-cut instrument for imposing “consensus” around values that are not theirs if not actually hostile to theirs, like “pacifying” the conflicts through recourse to repressive force and conformity to the ruling order.

The other focal point of dissatisfaction expressed at these rallies has been police repression. It would not be wrong to conclude that the rapid growth in the number of people on the streets today can be attributed to a reaction against the police violence that was used to repress demonstrations last week, especially in São Paulo. These demonstrations started out as protests against higher fares but they have expanded into protests in favor of the right to demonstrate. Some claim that the police used excessive force; others argue that the police are simply unprepared. They’re wrong, or they want to muddy the waters. The mere fact that the Brazilian government maintained its military police forces even after the demise of the dictatorship accounts for many things. And it is not a lack of preparation that police officers are displaying when they fire into a crowd of demonstrators at close range – they’ve been trained to do this every day in favelas and on the periphery of large metropolitan areas (except that the bullets there are not made of rubber). They are also accustomed to applying this repressive force against any working class movement that dares to go beyond the role of government cheerleader.

In short, in the ongoing counter-revolution that characterizes the bourgeois autocracy in Brazil (to recall Florestan Fernandes), the media monopolies engage in a steady effort to mold hearts and minds to the designs of capital and of the repressive police arm of a State that never relinquished its cruelest side. As such they have formed the secondary targets of these protests against fare hikes – secondary but more and more primary and also a new catalyst for the demonstrations now underway. These protests foreshadow a potential expansion of this dissent and an atmosphere of latent uprising against the two stronger sides, which work together to hold back class struggle and characterize bourgeois domination in Brazil today: the tremendous network of devices meant to forge consensus and the never-dismantled, always-augmented apparatus of repressive coercion.

Of course, for this potential to be transformed into a true wave of change, much more is necessary. The generations now in their forties and fifties took to the streets in the 1980s to demand “Elections Now!” and the end of the dictatorship, just as the generation from thirty-five to forty painted their faces and shouted “Collor Out!” in the early 1990s [calling for the impeachment of then-president Collor]. It is necessary for them to return to the streets now to fight for deep change, alongside their children. And this movement would surely grow if the unions called on their members to stop work and add their numbers to the next demonstrations. And if the homeless and the landless, impacted by upcoming mega-events and surrounded by armored vehicles and pacifying police units, would close ranks in unison with the discontent. And if the parties on the left, especially those that still believe that the National Congress is the stage for major struggles, would wake up and recognize that the streets play the central role. And if a coherent program of anti-systemic grievances would clearly show how fares go up, the police beat up, and the media chime in because this is how the sociability of capital works in our great “emerging” periphery.

It is up to us now to plant the flowers of a Brazilian spring in the asphalt of the streets, for winter has lasted too long in these sunny tropics.

* Marcelo Badaró Mattos is a professor at the Federal Fluminense University

Read more:

Editor experiences history in the streets, by Jaime Benchimol

José Murilo de Carvalho: the Brazilian people have woken up from their lethargy

‘More than narrating these events, we must live them intensely’ an interview with Valdei Araujo.